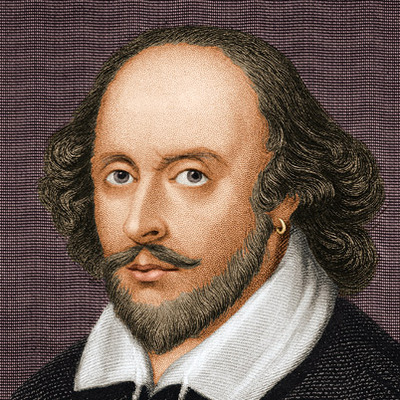

Alan Bradley, left; Bill Bryson, right.

It would have made a great story. If only the facts would cooperate.

Last night I finished listening to Bill Bryson’s book about Australia, In a Sunburned Country. I listened with joy to his elegantly turned phrases, self-deprecatory humor, and characterizations of the people and landscape. His dismay at the treatment of aborigines provoked me to care, too. At times Bryson’s tone veers to the suburbs of crass, and he inserts a few liberal rants, but overall I liked it very much.

As it happens, I also finished Alan Bradley’s latest Flavia de Luce mystery, Speaking from Among the Bones. Because it’s how I’m wired, I read through the acknowledgments, and there two thirds down the page were these sentences: Family, too, have been there to wave flags and shout encouragement at every way station, and I’d like to especially acknowledge …Bill and Barbara Bryson…

What? Bill Bryson in Alan Bradley’s family section? Crazy! I skipped out of bed to explore this connection. Alas, Bill Bryson, the author, is married to a Cynthia. Bill’s father, William, is married to an Agnes Mary. I can’t detect anything other than coincidence in the names.

My favorite excerpt from Bryson’s book is his description of how he sleeps:

I am not, I regret to say, a discreet and fetching sleeper. Most people when they nod off look as if they could do with a blanket; I look as if I could do with medical attention. I sleep as if injected with a powerful experimental muscle relaxant. My legs fall open in a grotesque come-hither manner; my knuckles brush the floor. Whatever is inside—tongue, uvula, moist bubbles of intestinal air—decides to leak out. From time to time, like one of those nodding-duck toys, my head tips forward to empty a quart or so of viscous drool onto my lap, then falls back to begin loading again with a noise like a toilet cistern filling.

And I snore, hugely and helplessly, like a cartoon character with rubbery flapping lips and prolonged steam-valve-exhalations. For long periods I grow unnaturally still, in a a way that inclines onlookers to exchange glances and lean forward in concern, then dramatically I stiffen and, after a tantalizing pause, begin to bounce and jostle in a series of whole-body spasms of the sort that bring to mind an electric chair when the switch is thrown.. Then I shriek once or twice in a piercing and effeminate manner and wake up to find that all motion within five hundred feet has stopped and all children under the age of eight are clutching their mothers’ hems.

Flavia’s humor is dry, more inclined to make me smile in appreciation than to laugh out loud. And tucked in unexpected places the whiz kid chemist wonders about life.

How odd, I thought: Here were these four great grievers, Father, Dogger, the vicar, and Cynthia Richardson, each locked in his or her own past, unwilling to share a morsel of their anguish, not even with one another.

Was sorrow, in the end, a private thing? A closed container? Something that, like a bucket of water, could be borne only on a single pair of shoulders?

Edit: I received a gracious and funny email from Mr. Bradley confirming that his Bill Bryson is not the American author Bill Bryson.