Invite evaluation.

I need it. We need it.

Feedback from faithful friends.

How am I doing?

Where could I improve?

Eager to protect, afraid of exposure,

unwilling to change: a miserable route.

Humility is the path to growth.

Invite evaluation.

I need it. We need it.

Feedback from faithful friends.

How am I doing?

Where could I improve?

Eager to protect, afraid of exposure,

unwilling to change: a miserable route.

Humility is the path to growth.

Bruce Marshall’s author blurb on the back cover:

Bruce Marshall is a dark, smiling man, fundamentally serious, four-square in appearance, definite in manner. He has a great fund of pity for humble, toiling people whose virtues are seldom proclaimed, a vigorous and delightfully malicious humor, and a savage dislike of bullies, stuffed shirts, humbugs and toadies.

Many of my favorite stories involve priests: G.K. Chesterton’s Father Brown; dear Mr. Harding in Anthony Trollope’s The Warden

; Father Tim in the Mitford books

and Father Tim novels

; Brother Cadfael in Ellis Peter’s medieval mysteries

; the priest in Jon Hassler’s Dear James

.

Father Smith is a Catholic priest in Presbyterian Scotland, a priest who prays daily for Scotland’s conversion. I don’t think I’ve ever read a novel with such a strong emphasis on Catholic theology, and, at first, I found it off-putting. But I discovered that I appreciated many of this humble man’s thoughts. I think any conservative would appreciate the struggle to hold on to the old ways.

When he had been a boy himself, Father Smith had longed to be grown up, because he had believed that it would be easier to obey our Lord as an adult than as a child, and he had been disappointed when he had found it was more difficult.

When he was happy, Father Smith always sang snatches from the psalms as he walked the street.

Always remember that you can’t see into other people’s souls, but you can see into your own, and so far as you really know there is nobody alive more wicked and ungrateful to Almighty God than yourself.

Father Smith felt that it was a pity that one ever heard anything at all on wireless sets, because it seemed to him that new inventions were coming out much too quickly, and that if amusements went on becoming more and more mechanized as they seemed to be doing, people would no longer require to use their intelligence to fill their leisure, and literature, poetry, and the drama would be pop goes the weasel per omnia saecula saeculorum…

…and those who weren’t weeping had a great distress on their faces because they knew that a great clumsy slice of man who had known all about God’s mercy would walk among them no more.

The book opens at the start of the twentieth century with the priests wondering how to respond to the first cinema in town. Father Smith baptizes two babies, whose lives we follow throughout the story. When the Great War begins, Father Smith works on the front line as a chaplain, hearing confessions and praying over the dead. His bishop predicts a spiritual revival will come out of the war, but Father Smith finds reality to be much different. What held my attention was Father Smith’s grappling with the tension from the static doctrines of the church and the rapidly changing culture.

I learned a host of Catholic nomenclature: sedilia (stone seats for the clergy), asperges (the rite of sprinkling Holy water), pyx (the container that holds consecrated bread), and pro-Cathedral (parish church temporarily serving as cathedral).

I wish I could remember who recommended this. I found it absorbing reading, but I have no desire to read it again. The cheerful humility makes me want to explore another book by Bruce Marshall.

The Holocaust was storm, lightning, thunder;

wind, rain, yes.

And Le Chambon was the rainbow.

— Jewish mother whose children’s lives were saved at Le Chambon

Let me digress: One habit served me well and introduced me to the story of Le Chambon. I read books with a soft lead pencil in hand. When a word, phrase, sentence or paragraph nudges me, I mark a line in the margin, | . When I read an unfamiliar word or one I can’t confidently define, I put a √ in the margin. And when I see a reference to a song, a painting, a book title, an event that I’d like to know more about I also use the √. I usually don’t stop reading to look further at the subject. But when I comb through the book a second time, writing down compelling quotes, etc. I will follow up on the check marks.

How did I find Lest Innocent Blood Be Shed? I had decided to cull out Barbara Tuchman’s sparkling book of essays, Practicing History

, from my library, a decision that still gnaws. Before I let it go, I transferred notes to my journal. In an essay entitled Mankind’s Better Moments Tuchman notes some astonishing accomplishments:

the enclosure of the Zuider Zee in the Netherlands adding half a million acres to the country;

the marvel of Gothic cathedrals;

Viking seamanship;

the perseverance of La Salle, who mastered eight languages before he set off exploring;

William Wilberforce’s work to abolish slave trade;

Le Chambon, a Huguenot village in Southern France devoted to rescuing Jews. √

Le Chambon? I had heard of Huguenots—French Protestants—but not Le Chambon.

Intrigued, I found this clip on YouTube:

And I found Philip P. Hallie’s book, Lest Innocent Blood Be Shed. The book is essentially a biography of the Reformed pastor, André Trocmé and his wife, Magda. Trocmé’s belief in God was at the living center of the rescue efforts of the village xxi. Le Chambon was a remote mountain village, predominantly Protestant (Reformed and Plymouth Brethren) in a predominantly Catholic country. The Trocmés were unshakably committed to obeying the Sermon on the Mount 28.

In practice this means that the village rescued between 3,000 and 5,000 Jewish refugees during the Holocaust. They kept many Jewish children at a private school; some family groups stayed until they could seek refuge in Switzerland. All the villagers took great risks, but they considered harboring others more important than their own safety.

“Look hard for ways to make little moves against destructiveness.” — André Trocmé

Trocmé attended Union Theological Seminary in 1925 (five years before Dietrich Bonhoeffer was there) and found the Social Gospel too secular, too rational, lacking piety. Like Bonhoeffer, Trocmé lived intimately with those he shepherded.

For the rest of his life he sought another union [an organization he belonged to as a child during WWI], another intimate community of people praying together and finding in their love for one another and for God the passion and the will to extinguish indifference and solitude. From the union he learned that only in such an intimate community, in a home or in a village, could the Protestant idea of a “priesthood of all believers” work. Only in intimacy could people save each other. 57

A recurring motif in the book is that André Trocmé gave himself. He gave himself to his people, visiting them in their homes regularly. He gave himself to his community by his involvement in their lives. When he came home his children rushed him, enveloping him in hugs because he brought himself to them. Hallie expatiates on this theme in one of the most profound passages in the book:

When you give somebody a thing without giving yourself, you degrade both parties by making the receiver utterly passive and by making yourself a benefactor standing there to receive thanks—and even sometimes obedience—as repayment. But when you give yourself, nobody is degraded—in fact, both parties are elevated by a shared joy. When you give yourself, the things you are giving become to use Trocmé’s word, féconde (fertile, fruitful). What you give creates new, vigorous life, instead of arrogance on the one hand and passivity on the other. 72

At one time, Trocmé is asked whether another group struggling in WWII should practice non-violent resistance. His response was that a foundation first has to be laid before such a tactic can be efficacious. Trocmé, along with Pastor Edouard Theis and schoolteacher Roger Darcissac had poured their lives into resisting evil and teaching their neighbors before such visible means of resisting became necessary.

I tend to look for perfect heroes and tidy endings. I was sad to read that a personal tragedy reduced Pastor Trocmé’s faith and that Mme Trocmé seemed to hold faith at arm’s length even as she worked indefatigably.

Writing about this book brings threads of recent events together: Today, April 9th, is the anniversary of Dietrich Bonhoeffer’s death. There are striking similarities and certain differences between André Trocmé and Dietrich Bonhoeffer. As I look at the photo of the Trocmés above, Magda Trocmé reminds me of Edith Shaeffer, a different kind of rescuer, who died on April 6th. And finally, the news of Rick Warren’s son’s suicide on April 5th coincides with a Trocmé family tragedy.

Ever curious, I wondered where the surviving children were. I discovered that Nelly Trocmé Hewett, 85, was giving talks last October and is scheduled to speak tomorrow at Macalester College in the Twin Cities. How immensely would I love to be in that audience.

I love 5MinutesforBooks.com’s feature What’s on Your Nightstand? It’s fun to get a snapshot of what people are reading. Clearly, I did not tidy up my stack of books on the nightstand. I can’t go into much detail, because of time constraints, but here is the stack I am working through. I ran out of my favorite Post-It Flags, as you can see by the pencils stuck in the books. Shame.

• Real Marriage, by Mark and Grace Driscoll is on loan from my son and his wife. I want to read parts of it aloud with my husband…someday!

• Barely visible, the tiny sliver of blue, is Fit to Burst by Rachel Jankovic. This young mom has an abundance of wisdom that reaches far beyond homemade granola bar recipes and stars on chore charts. I like to consume it in small bites.

• The back cover showing, Shadow of the Silk Road, by Colin Thubron, is my current travel book. In this book Thubron travels from Xian, west of Shanghai, to Antioch in modern day Turkey. This is my third Thubron; I’m already inclined to like his writing. But I’m not sure he’ll be able to entrance me like Rob Gifford did in China Road.

• The generic black journal is my commonplace book. This is my fourth identical journal, purchased at WalMart, in which I write down quotes, phrases, words, book and DVD titles, and similar musings.

• The Sweetness at the Bottom of the Pie, a Flavia de Luce mystery by Alan Bradley, has been borrowed for far too long. I listened to the highly excellent audio version, but wanted to copy quotes from it. Which involves a re-reading with some skimming. So this title is the most guilt-inspiring one.

• Black bound Kindle rests on Flavia. I read the sample portion of Booked, Literature in the Soul of Me, by Karen Swallow Prior. An email reminded me that I had an unused gift card from Amazon, so I purchased the book today. Although I keep acquiring Kindle books, I haven’t read much except the Bible on it in February.

• The orange spine of Scrolling Forward, Making Sense of Documents in the Digital Age, by David Levy, is a book that simultaneously provokes groans and stubbornness in me. I was “Currently Reading” this on Goodreads on September 9th! The author, after finishing a Ph.D. in computer science, majoring in Artificial Intelligence, moved to London to study calligraphy for two years. That alone makes me like him. And the dedication in Hebrew. But, this book from 2001 is outdated. And for some reason I can’t ditch it. My persistence—foolish or not—was rewarded in chapter 10 with a great story about the 1989 San Francisco earthquake and the author’s assignment for a Hebrew class to translate Psalm 104:5. I have twenty pages left and I’m determined to finish. But the joy left a while back.

• Top of the pile is This Rich and Wondrous Earth, a Memoir of Sakeji School, by Linda Moran Burklin. I’ve read Wes Stafford’s book Too Small to Ignore and several magazine articles revealing abuse and mistreatment at African boarding schools for missionary kids. This book is not about that. Linda’s book has a good-natured humor that acknowledges the hardships and difficulties, but also points out the benefits she received and the fun she experienced. I have to admit that the tight regimen and censored letters home has reminded me of prison. Last night we read a few pages aloud after dinner about a baptism that had us all laughing. It sounds sacrilegious, but it truly was a funny baptism story. I know of an MK who found Linda’s book very therapeutic. I’m eager to finish it and pass it on to my cousin who was at a different African boarding school.

• There is a secondary pile behind the towering one with two books: Muriel Barbery’s The Elegance of the Hedgehog and John Stott’s The Birds Our Teachers. You might call this the “Meaning To Get To” Pile.

You are welcome to join the crew over at 5MfB or just write in the comments. What are you reading?

Politics, work, love, sexual appetites and revolt: these all have some great quotes in this lengthy section. My favorite involves collywobbles. Even though I steadfastly discarded some great quotes from this post, it is long. Which phrase jumps out at you?

Two questions arise.

In the first place, what is power?

And secondly, where does it come from?

Of King Louis-Phillipe

He was careful of his health, his fortune,

his person and his personal affairs,

conscious of the cost of a minute,

but not always of the price of a year.

Harmony enforced for the wrong reasons may be more burdensome than war.

Nothing is more dangerous that to stop working.

It is a habit that can soon be lost,

one that is easily neglected and hard to resume.

Every bird that flies carries a shred of the infinite in its claws.

In the forming of a young girl’s soul

not all the nuns in the world can take the place of a mother.

Work is the law of life, and to reject it as boredom

is to submit to it as torment.

Sloth is a bad counselor.

Crime is the hardest of all work.

Take my advice, don’t be led into the

drudgery of idleness.

I encountered in the street a penniless young man who was in love.

His hat was old and his jacket worn, with holes at the elbows;

water soaked through his shoes,

but starlight flooded through his soul.

It’s bad to go without sleep.

It gives you the collywobbles.

Among the most great-hearted qualities of women is that of yielding.

Love, when it holds absolute sway, afflicts modesty with a kind of blindness.

The risks they run, those generous spirits!

Often they give their hearts where we take only their bodies.

To Marius, the purity of Cosette was a barrier,

and to Cosette his steadfast self-restraint was a safeguard.

The happiness of quarreling simply for the fun of making up…

At the end of life death is a departure;

but at life’s beginning, a departure is death.

He remarked now and then, ‘After all, I’m eighty’ —

perhaps with a lingering thought that he would come to

the end of his days before he came to the end of his books.

[A waterfall of words describing the elements of revolt]

Outraged convictions,

embittered enthusiasms,

hot indignation,

suppressed instincts of aggression;

gallant exaltation,

blind warmth of heart,

curiosity,

a taste for change,

a hankering after the unexpected;

[snip] vague dislikes,

rancours,

frustrations,

[snip] discomforts,

idle dreams,

ambition hedged with obstacles…

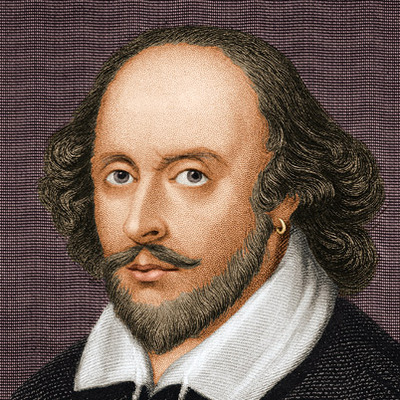

For more than a decade I’ve been thinking, I really want to read through all of Shakespeare’s works. It’s like the idea that someday all my photos will be in scrapbooks. Happy thought. Inspired by my sister-in-law who recently read a whole slough slew of Shakespeare, and suspecting that it would be like cleaning a cupboard—it feels so good that I want to keep going—I plunged into The Comedy of Errors. More on that, later. But it was true: drinking the language was drinking a Caramel Macchiato. I had to read sections more than once to tease out the meaning, but that was offset by laugh out loud lines and the satisfaction of fitting words.

How many plays did the bard write? Thirty-seven. I’ve read eleven, but I’d like to read through them all fresh again. If I averaged one play a month, I’d hit pay dirt by the end of 2015. I want to read the poems too, but that’s another thing.

Although I own a Complete Works of Shakespeare, I find it annoying. It is formatted in two columns and whenever there isn’t quite enough room at the end of the line the leftover is printed on the line above it. You can get the complete works on Kindle for $1.99, but I don’t want to read from the Kindle. I want an edition with footnotes on the same page, a running synopsis, explanatory notes. I want to converse with Shakespeare via pencil marks in the margin. I want a book for a student. I have a few student editions: Cambridge University Press, Oxford, Modern Library. I’m using my Paperbackswap credits and looking for $0.01 Amazon deals to fill in the gaps.

I’m going to try to read each play in one sitting, with a short intermission if needed. If I saw the play, I would sit through the all the acts in one performance.

Comedies

All’s Well That Ends Well

As You Like It

The Comedy of Errors √

Cymbeline

Love’s Labour’s Lost √

Measure for Measure

The Merry Wives of Windsor

The Merchant of Venice √

A Midsummer Night’s Dream √

Much Ado About Nothing

Pericles, Prince of Tyre

Taming of the Shrew √

The Tempest √

Troilus and Cressida

Twelfth Night √

Two Gentlemen of Verona

Winter’s Tale

Histories

Henry IV, part 1 √

Henry IV, part 2

Henry V √

Henry VI, part 1

Henry VI, part 2

Henry VI, part 3

Henry VIII

King John

Richard II

Richard III

Tragedies

Antony and Cleopatra

Coriolanus

Hamlet √

Julius Caesar √

King Lear

Macbeth √

Othello √

Romeo and Juliet √

Timon of Athens

Titus Andronicus

In The Comedy of Errors two sets of identical twins converge at Ephesus. They were separated in a shipwreck, and both twins share the same names. The man [Antipholus] and his slave [Dromio] (from Syracuse) are searching for their lost brothers [Antipholus] and his slave [Dromio] (from Ephesus). You can imagine the confusion.

Early in the play these Antipholus-S speaks poignant words of one on an impossible quest:

I to the world am like a drop of water

That in the ocean seeks another drop…

When Antipholus-S finds his supposed slave, Dromio-E, hasn’t fulfilled the commands he gave him, he begins to beat him. Dromio-E is astonished!

What mean you, sir? For God’s sake hold your hands.

Nay, an you will not, sir, I’ll take my heels.

I find this word play (hold, hands, take, heels) charming. Shakespeare’s rhythms also delight me. Saying the next sentence ten times would not quench the joy it brings.

Dromio, thou Dromio, thou snail, thou slug, thou sot.

When her supposed husband is acting cold and distant, Adriana has some poignant lines. When her sister shushes her, Adriana exposes the discrepancy in how we view trouble, depending on who owns it:

A wretched soul, bruised with adversity,

We bid be quiet when we hear it cry.

But were we burdened with like weight of pain,

As much or more we should ourselves complain.

This is a comedy, which means there is a happy ending. Everything is sorted out and brothers—two sets—are reunited with much embracing and feasting.

There are some great quotes about child raising in this section, some heart-wrenching. We are introduced to Gavroche, one of the most winsome characters in literature. Also some great thoughts on work/contemplation/sloth. Any bibliophile will love the charming Monsieur Mabeuf, a man who describes himself not as a royalist, a Bonapartis, or an anarchist—simply as a book-ist.

Give a youngster what is superfluous,

deprive him of what is needful,

and you have an urchin.

All monarchy is in the stroller,

all anarchy in the urchin.

To wander in contemplation,

that is to say, loiter,

is for a philosopher an excellent way

of passing the time.

He was one of those children who are most to be pitied,

those who possess parents but are still orphans.

…hypochondriacs…who spend their life dying…

Nothing so resembles an awakening as a return.

He knew Italian, Latin, Greek, and Hebrew,

but the four languages served him

for the reading of only four poets,

Dante, Juvenal, Aeschylus, and Isaiah.

To err is human,

to stroll is Parisian.

He was always down to his last penny,

but never to his last laugh.

‘Peace,’ said Joly, ‘is happiness in process of digestion.’

Old people need love as they need sunshine; it is warmth.

He never left home without a book under his arm,

and often came back with two.

(Photo credit: Wikimedia Commons)

This morning, reading a reference to El Greco’s stormy sky over Toledo, I was taken back ten years.

Holy Toledo! somebody exclaimed. My son, in the neighborhood of eleven years old, asked “Why is a city in Spain holy?”

His grandpa stared—the laser beam—at him. “City in Spain?” He looked away, sighed, shaking his head. “Try city in Ohio.”

Now it was Collin’s turn to demonstrate incredulous. We had been reading about the Auto-da-Fé. If he knew anything, he knew that Toledo was a city in Spain. He’d never heard of Toledo, Ohio.

They both looked at me.

Steady, I thought, steady. I smiled.

You are both correct! Toledo is a city in Spain and a city in Ohio.

That neither of them knew both facts surprised me. Americans, I think, tend to speak only English and be familiar only with America. But many classically-educated kids know details of the Peloponnesian War but not a rudimentary fact about their own state. (That, my friend, is not a theoretical example.)

It makes me curious? Did you know both* locations of Toledo?

*Per Wikipedia, Toledo is a also district in Belize, a municipality in Brazil, a town in Colombia, and a city in the Philippines, in Uruguay, in Illinois, Iowa, Oregon and Washington.

May I say that I thoroughly enjoyed the wandering Waterloo section? I only knew the rudiments of this history and was happy to learn more details. The battle observations astonished me.

Ruins often acquire the dignity of monuments.

There is no logic in the flow of blood.

They rode steadily, menacingly, imperturbably,

the thunder of their horses resounding

in the intervals of musket and cannon-fire.

[The 3 syllable-4 syllable-5 syllable cadence of adverbs ignites me.]

A disintegrating army is like the thawing of a glacier,

a mindless, jostling commotion,

total disruption.

…to incarnate irony at the mouth of the grave,

staying erect when prostrate…

War has tragic splendours which we have not sought to conceal,

but it also has its especial squalors,

among which is the prompt stripping of the bodies of the dead.

The day following a battle always dawns on naked corpses.

She did all the work of the house, beds, rooms, washing and cooking;

she was the climate of the place, its fine and foul weather…

Darkness afflicts the soul.

Mankind needs light.

To be cut off from the day is to know a shrinking of the heart.

Where the eye sees darkness the spirit sees dismay.

…the haggard gleam of terror…

A doll is among the most pressing needs

as well as the most charming instincts of feminine childhood.

To care for it, adorn it, dress and undress it, give it lessons,

scold it a little, put it to bed and sing it to sleep,

pretend that the object is a living person—all the future of women resides in this.

Dreaming and murmuring, tending, cossetting, sewing small garments,

the child grows into girlhood,

from girlhood into womanhood,

from womanhood into wifehood,

and the first baby is the successor of the last doll.

A little girl without a doll is nearly as deprived

and quite as unnatural as a woman without a child.

So Cosette made her sword into a doll.

Like all children,

like the tendrils of a vine reaching for something to cling to,

she had looked for love,

but she had not found it.

Paris is a whirlpool in which all things can be lost,

sucked into that navel of the earth

like flotsam into the navel of the sea.

…this hubbub of little girls, sweeter than the humming of bees…

To appear at once troubled and controlled in moments of crisis

is the especial quality of certain characters and certain callings,

notably priests and members of religious communities.

Laughter is a sun that drives out winter from the human face.

I must clarify that my nightstand is a bag of books, because I’m at my second son’s house helping out after the birth of Riley, his third son. And since babies trump books any day of any year, here is the handsome boy, our sixth grandson.

And here is a picture of my “nightstand.”

Yep. I think I brought 17 books with me. Some I’ve read, but need to copy parts into my commonplace book. Because a photo like the one above would drive me wild (I can’t see the titles, I’d be saying to my computer) here are a few on a tottering stack.

Let’s just work down this pile, shall we?

:: Frank Delaney’s Ireland :: I had a hard time settling into this story in the print version. When I downloaded the audio book, I couldn’t leave the book. Sometimes I read along, but mostly I used the book for a quick way to note sentences to copy later. If you love word origins, Delaney is your author. Beginning before Saint Patrick and going through the Easter Rising, the oral tradition of Ireland, intertwined with the narrative, make this a great read. I firmly believe that any Frank Delaney title must be heard. Delaney reads his own books, and with his background in broadcasting, his renditions far surpass any other “read by author” audio book.

Then she polished [the battered boots] to a shine, and they stood inside the back door, ransomed, healed, restored, forgiven. p. 58

:: Shakespeare’s Comedy Of Errors :: Making good on my promise to fill in the gaps in my Shakespeare. I haven’t started yet, but I’m going to take a tip from my sister-in-law: read his plays in one sitting.

:: Patrick Taylor’s An Irish Country Girl :: I recently engaged the services of a new financial adviser; within two minutes of our appointment we were talking books, and he gave this book to me. Nice, huh?

:: Victor Hugo’s Les Miserables :: This was December’s big read, but the book is not finished with me yet. I would like to go back and read some of the underlined parts again. And perhaps do a few more blog entries like this one.

:: Ronald Doah’s Fantastic Mr. Fox :: I test drove this with my other set of boys. They loved it. I thought I’d try with these guys.

:: Larry McMurtry’s Roads : Driving America’s Great Highways :: A travel book on driving the interstates was just enough quirky to capture my attention. This best reason to read this book is all the references to other travel books. The author states that he owns and has read three thousand travel books. And I will ever be grateful for McMurtry’s phrase, a skim-milk light.

:: Marcel Proust’s Swann’s Way :: Capitalizing on the momentum from Les Mis, I thought I’d tackle another huge French novel, the first volume of Remembrance of Things Past. This version is translated by C.K. Scott Moncrieff, about whom–and about the translation work– I read in Russell Kirk’s memoir, The Sword Of Imagination

. I’m finding it tough sledding, but I’m plowing through hopeful for some happy rewards.

:: Muriel Barbery’s The Elegance of the Hedgehog :: Another title from my new stockbroker. Any thoughts from you who have read it?

:: Lawrence Anthony’s The Elephant Whisperer :: My friend Rachel sent this to me when she figured out I was hip deep in books on Africa. It looks delightful, and if I learn enough about elephants I can reckon it as a science read!

:: Linda Burklin’s This Rich & Wondrous Earth :: A memoir of Sakeji School, a British boarding school in Zambia. Burklin captures the tension of trying to fit into a new environment and stay out of trouble. I’m only a few pages into this, but I’ve enjoyed what I’ve read so far.

:: Anthony Trollope’s Lady Anna :: I listened to this Librivox recording on the six hour car trip up here. And I’ve fallen asleep listening to it every night. The plot and themes remind me of the very first Trollope I read, An Old Man’s Love

, wherein after a (fatherless) young woman gives consent to a suitor, a more attractive man comes courting. Does keeping your word apply to an engaged couple?

So what about you? Whatchareading?